Until I came to Ukraine, I only then began to truly gain some understanding of the country (and certainly there are many things I still don’t know about). Few are surprised now about how many lies are spread about Ukraine. Part of the success of this, such as Western journalists believing lies from the Kremlin that people like Girkin/Strelkov and Prighozin have denied, is because of the lack of understanding about Ukraine. I read a lot about politics and history before coming to Ukraine, and even with that knowledge, I still learned a considerable degree of knowledge. It’s one thing to read about a topic, or hear second hand, but to experience it directly and through real conversations with actual Ukrainians, is entirely different.

In many ways, you cannot fully grasp a country unless you really delve deep, live there, talk to lots of different people from the country, learn some of the language(s), etc. Now I’m not saying you have to do all of these to comment on Ukraine or have a good understanding, though certainly without experiencing the country it will be more abstract. But certainly, too many people who present themselves as actual experts ‘do not do these things at all. The key is to understand that you have gaps, I admit to having gaps in my knowledge, but I’m still learning things.

The problem is that most people just read a few articles, and run on stereotypes, without actually investigating. Why do they do this? Too many “Ukrainian experts” or “journalists” are insufficiently knowledgeable about Ukraine! For example, they are often also russia watchers sometimes not even in russia! I remember a CNN job for a russia reporter that didn’t even require knowing the russian language. Basically, from ignorance about Ukraine, lies can easily take hold. Our state of experts is poor, and normal people just simply aren’t given the right information.

This definitely applies to other countries. How many of us really understand the intricacies of most countries’ history? We don’t, and we cannot expect everyone to become an expert. We, therefore, expect our experts and journalists to do a good job. It also means we have to be careful when trusting experts (like I have said).

In light of this, I’m going to go through a few of the various things that many people still get wrong about Ukraine.

- The Country’s Internal Linguistic and Political Complexities

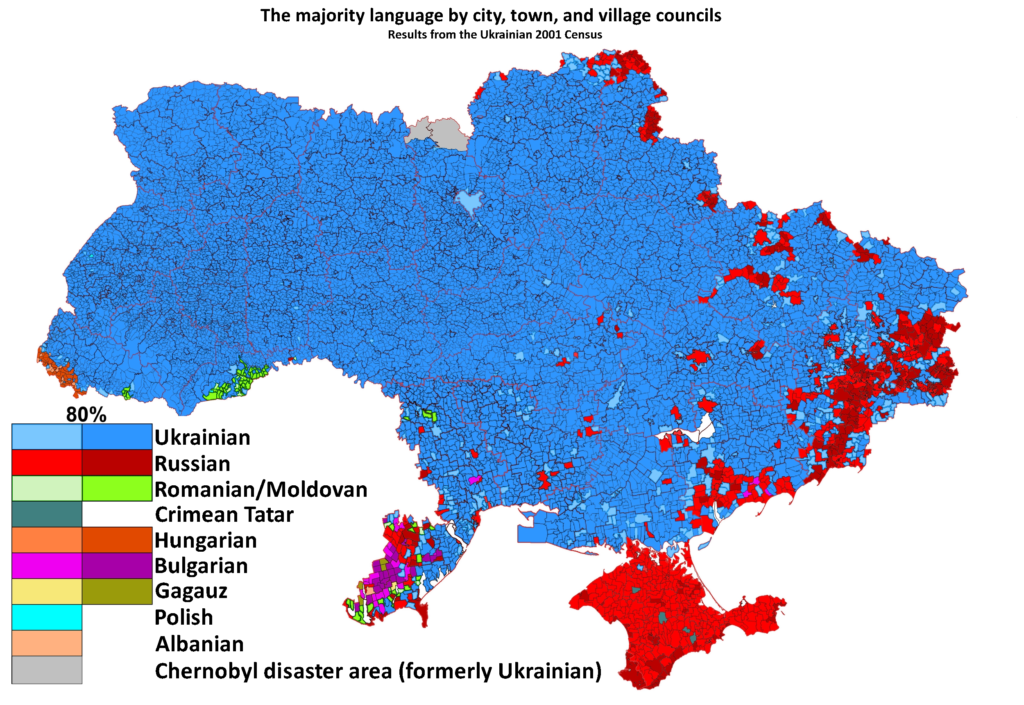

Now, I talked a bit about this before when I discussed the diversity of Ukraine. The linguistic situation is not “russian speaking east” vs “Ukrainian speaking west”, most people can speak both, and many mix them together. In addition, Russian speakers do not necessarily mean pro russian.

I was already aware of this when I came to Ukraine for the first time. However, when I met people in Kyiv, who spoke russian, yet had gone to the front in 2014, I really understood first-hand that the language has no bearing on politics. Sure, most pro-russians will almost certainly speak russian, but it’s definitely not an equivalent relationship.

I never quite grasped the different dialects and linguistic diversity before I arrived. Hearing about the Hungarian minorities in Zakarpattia, the Romanians in Chernivsi, and the truly linguistically diverse region of Bessarabia, was fascinating. There are a lot of complexities to this of course, and issues around linguistic assimilation vs. respecting minority languages. However, to go through different towns and see signs in two languages at once, showed me how Ukraine is very diverse. But again, just because people speak these languages does not mean they are not supportive of Ukraine as a country or don’t consider themselves Ukrainian.

A more accurate divide in politics is around different forms of Ukrainian identity. This has radically changed since 2014. Since then more and more people have come around to the idea that Ukrainians should move away from russia. This would involve ideas such as that the government and society should encourage the Ukrainian language over russian, teach its own history away from the Soviet past, and pursue further derussification. Whereas before many, especially those with ties to russia (which is a lot of people, many Ukrainians have some relative in russia, friends from russia, perhaps worked for russian companies, etc), felt that russians and Ukrainians were, well not necessarily brotherly nations (though some did), but most likely that at least they could work together, trade together, and be at peace.

Certainly, I’ve met some older folks who were quite the russophiles. Perhaps they didn’t love the promotion of Ukrainian, feeling russian language was fine. Maybe they felt nostalgia for the USSR (though usually, this was because they lost a lot or were younger and healthier, or see their children and grandchildren worry about things they never had to i.e. flats, jobs, etc. which used to be guaranteed). But now, many of them say they don’t like the russians, they try to switch to Ukrainian and support the fight against the russians. They’ve felt betrayed and hurt.

So the point is that language and political identity are far more fluid, and they change a lot over time. People who may have even considered themselves a Soviet citizen or russian-Ukrainian before may have rejected this identity over time. Many of those who before never cared about the Ukrainian language have often switched over. Things change, because politics is complicated, and identity is too. You won’t fully grasp this though without talking to Ukrainians and their own experiences.

- How Much Ukraine Has Changed

Speaking of things that change, Ukraine has changed a lot even in the four years I spent here.

Going back just ten or so years we see massive changes. For example, in 2010, Russia did a joint military parade in Kyiv! This was normal. And many people felt the sense of “Nash” and if you told someone even in 2012 that Ukraine would be at war with russia, they’d think you were crazy.

But it’s more than just relations with russia. Corruption has been getting a lot better since 2014. I hear stories of corruption in the past and how overt it was. While it does still happen at different levels, such as a policeman taking a bribe, or the big busts of top politicians, it’s nowhere near as bad as it used to be and is constantly getting better. The fact these stories make the news now shows how things are changing. Additionally, more people are fully aware and supportive of the idea of not supporting this culture of bribery, which used to be a necessity in the 90s and early 00s to get anything done. I’ve actually never been asked for a bribe even in four years, though I am privileged enough to afford private services most of the time, whereas it’s often in underfunded state services where bribery happens due to overworked and underpaid staff. This is why a lot needs to be done on cracking down on the “grey” economy, cash in hand work, reducing full-time employees’ taxes so they have a reason to pay them, and making services better as a result.

In terms of the economy, the IT Sector has exploded and is still growing, as I talked about before as well. The education in STEM is very good in Ukraine, and many people learn IT-related skills to earn good money in Ukraine. Some outsourcing, and some start-ups, you can find whatever really here. Stereotypes that Ukrainians are all peasant farmers or factory workers are far from accurate, especially among people under 40. I feel many people are not aware of that, and I certainly didn’t grasp the scale until I came here, teaching English to various companies in Kyiv, all doing very interesting projects and making a lot of money. Unlike the old-school companies, they have a lot more supportive workplaces as well as modern practices.

Further to this, the restaurant and bar scene in many cities has certainly grown and sophisticated. Of course, in the context of the war, Kyiv and other cities that are under strict curfew struggle. However, I was recently in Lviv and noticed there are so many more places to eat and drink than there used to be when I first arrived. Unfortunately, I suspect a lot are places that moved to Lviv due to the war.

Social attitudes as well are a big one. People often like to talk about how in Eastern Europe everyone is a racist, traditional, religious, etc. Well, I’m going to tell you that assuming this is everyone is straight-up stereotypical. Sure, you speak to some people, especially the older generation, and more rural people, you may tend to find religious people, very socially conservative attitudes, etc. And yes, some polls, especially pre-full scale invasion, don’t have Ukraine as the most tolerant country (though it’s actually more tolerant than other European countries in some areas like anti-Semitism according to other polls).

Things are changing, with more people becoming more accepting. There are bigger and bigger conversations about LGBT+ communities, especially as many are defending the country, which helps normalise them. We see similar discussions regarding social attitudes towards sex, gender, race, etc. Yes, I’ve heard stories of people experiencing racism and homophobia, though I also have in the UK, and some attitudes I heard here made me uncomfortable. However, I’ve also spoken to very tolerant people, especially among the younger generation who I would say are very small l libertarians. Let’s not judge too much when we consider it wasn’t that long ago in Western countries, such as the UK, that gay people couldn’t marry (or even legally exist if we go back not even 50 years).

Because people lack knowledge about how Ukraine is changing, they rely on stereotypes in their minds about Ukraine. The ways films and TV shows always show Ukrainians as criminals or prostitutes, or perhaps a journalist who had a trip in the 90s fill peoples’ heads. If you don’t pay attention to the changes in countries in general, you run on stereotypes and falsehoods, which cloud your judgement.

- The History, Culture, And Geography of Ukraine

What do most people think about when they hear Ukraine (at least pre-war?)

Chornobyl? Shevchenko (the footballer, not the national poet)? Klitschko brothers? “Kiev”? That it’s near russia? Was formerly part of the USSR?

So many people in the West, at least before the last year, usually rattled off one of these things about Ukraine. Even if they had heard of Kyiv or maybe Odessa or Lviv, they wouldn’t know what they were like. They don’t realise how beautiful it is, and neither did I. Kyiv, with its tree-lined central streets and true metropolitan feel, the seaside town of Odessa with a distinctive atmosphere and culture owing to the ports and Jewish presence, and the historical Lviv which blows me away every time I visit, among many other excellent cities in Ukraine. They don’t know about nature in say, Kherson oblast coast, or the mountains in the Carpathians, the dense forests of northern Ukraine.

There are several problems. One is that often Ukraine is just lumped with russia or called a “post-soviet” country, conjuring images of grey blocks of flats and misery. I talked about the beauty of Ukraine a lot before, and don’t need to repeat too much there, but not only is the country itself so beautiful and geographically diverse, you’ve got a massively rich history of Ukraine that is not merely part of russia. For example, Kyiv Rus, the Hetmanate, the cossacks, the Haydamarky uprising, and the Ukrainian National Republic between 1918-21, are just a few examples and all so fascinating and parts of understanding modern-day Ukraine. Effectively, it leads to a form of imperialistic thinking, reducing Ukraine to a footnote of russia.

Another concern is that by reducing a huge country, with a sizeable population, to a few stereotypes, again, people lack the understanding of the war now, the struggle for Ukraine’s independence, and just don’t have much of a positive attitude to Ukraine. This leads them to imagine it as sad and everyone wanting to leave, writing off their desire to fight, or just simply not caring. Without experiencing this country, without at least learning more, you can’t really be in a position to judge or comment on it.

- The Affects of the Soviet, and Post-Soviet, Hangovers

Most people may know that after the USSR, things were difficult. That’s usually about the extent of the knowledge they have. This can lead to lazy thinking regarding solutions and insight like “Why don’t they just make the country less corrupt”?

This is actually not entirely unique to Ukraine, though it is a particular problem as Ukraine is attempting to hit the EU criteria. Belarus, for example, may not care on an institutional level about these problems. The Baltics, especially Estonia, have made greater strides against these problems, in no small part due to EU membership.

There are many problems still, regarding efficiency for example, which affect the experience of many state institutions and the minds of people who used to work for social institutions and are now in the private sector. The love of stamps, physical paperwork, and running around various offices to do a simple task is diminishing but it is still there sometimes (especially if you’re a foreigner). More than that though, I think a bigger problem is that the Soviet system didn’t encourage imagination, going beyond your remit, and there was not a sense of competition for certain public services. Now, Ukrainians can be very, very imaginative and creative, finding new solutions, and there are a lot of very innovative individuals, politicians, and companies here. But, this does permeate certain attitudes in some institutions and individuals.

The second half of this problem is the post-USSR wild 90s. I think few of us in non-communist countries understand just how radical this change one. Overnight, the idea of the collective good over the individual disappeared, now anyone could become a businessperson, and in fact, you had to find ways to survive. The support that was promised to you disappeared overnight, and to get anything done, you had to navigate an entirely new and chaotic system. This post-soviet reality confirmed some of the worst things about capitalism, and unfortunately, some people adopted a very self-interested attitude or at least did so out of necessity. Many of us in the West know that if you run a business, you have to be good to your staff and customers because benefiting them benefits your business. Whereas a lot of the wild 90s in the countries that were now facing capitalism for the first time, capitalism with effectively no regulation, fostered a very selfish form of capitalism, out of necessity. Again, this has changed among the younger generation who grew up with capitalism as the norm, have more experience of Western style business, have travelled west more, learned English etc.

The point is that without talking to people about both the Soviet times and the 90s, which both had less than desirable aspects in very different ways, you won’t understand some of the problems that Ukraine, and other countries, face. And it is easy to come in as a Westerner and go “Oh, just clean up corruption, get rid of the oligarchs, done” because that oversimplifies the solution. Everyone in Ukraine knows that and most want that. The problem is how to actually and effectively do it because the problems exist as a result of both the Soviet and post-collapse realities and the institutions that were created in these periods. If you just replaced one person with another, the problems won’t go. Russia transitioning from Yeltsin to the Putin era did that. It requires a range of policies to tackle corruption at multiple levels, reshaping institutions, further digitalisation (something which is fantastic here to be honest), and, honestly, taxation of the hyper rich, and fostering new attitudes.

4) How Some Things are Actually Better Here Than in the West

The last point was a bit depressing, so I want to end on a more positive note some things are better here.

I mentioned digitalisation in the last post, this is very true. The government app Diia, which allows you to view multiple records, pay taxes, claim money for your damaged home from the war, check speeding tickets, records, vote on opinion polls, and even play a bayraktar game, among other things, is a godsend in efficiency and transparency. Private companies like Monobank, which has no physical locations, is the best bank I have ever dealt with, allows for speedy transfers, and everything is done via the app. Also, so many places don’t require cash anymore. It’s very rare to need cash apart from in a few villages, but even then they usually accept some form of bank transfer. Government communications are increasingly online, and not requiring the sending of letters and two week waits. The same for banks and other businesses.

Pre-war, there was never really problems finding accommodation. While for many, accommodation in big cities may cost a lot if you’re used to wages outside of the city (the rural and urban divide is noticeable), there is never a lack of it at least like in the UK or Ireland where you have to sometimes wait just to find something and compete with hundreds of other applicants. This was true EVEN IN KYIV!

Job hunting is incredibly speedier, with none of the two month of waiting for a response like we see in the UK even DURING THE WAR. Especially in the IT sector.

Customer service in hospitality is actually incredible and often better than in many Western countries.

Food quality is better: fresh fruit and veg have flavour, are sourced within the country, and cost a fraction of the price, and a lot of meat from fresh markets and things like that are, well, meat, not water and preservatives.

You won’t experience any of this without coming here, and I hope that those of you reading this who have not will be able to one day.

Leave a Reply