On the second of July, I had the pleasure of returning to the Carpathian Mountains and the Shypit festival. This is a festival of sorts in the depths of the mountains, going back thirty years now. I’ve attended a few times, but last year, Vice News turned up to report on this festival, and frankly, I hated the coverage of it. My wife has attended approximately fifteen times, I know people who have gone every year since the 90s, and the great “journalists” decided to make it as clickbaity as possible, making it out to be some mass drug fest. I want to rectify that.

This writing will incorporate my personal experience of this festival, some history, thoughts on the act of celebrating a festival during a war in the very same country, and more. It is one part an overview of the festival, one part a kinda gonzo write-up of my time there, with reflections on experiencing a festival in the middle of a war.

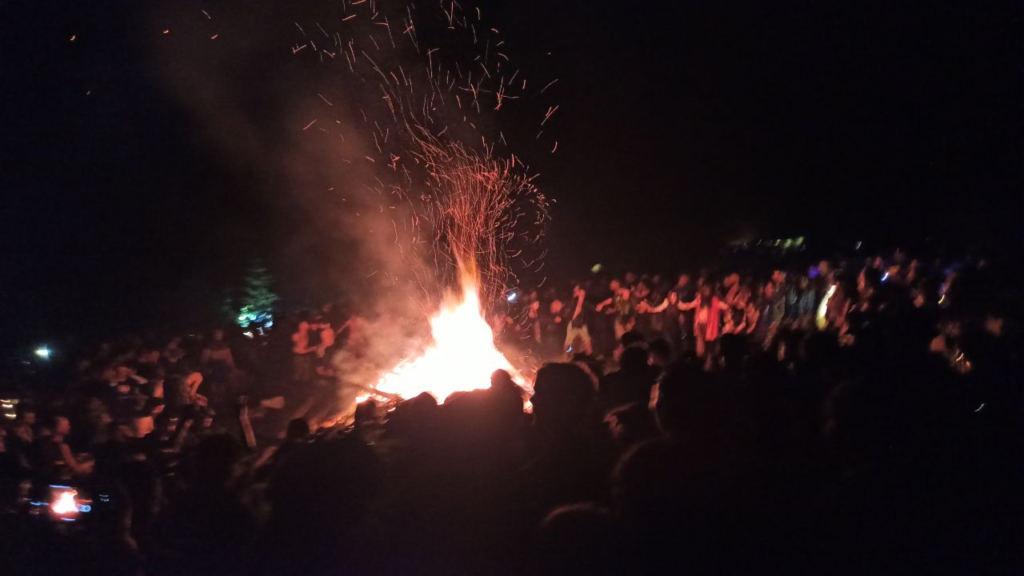

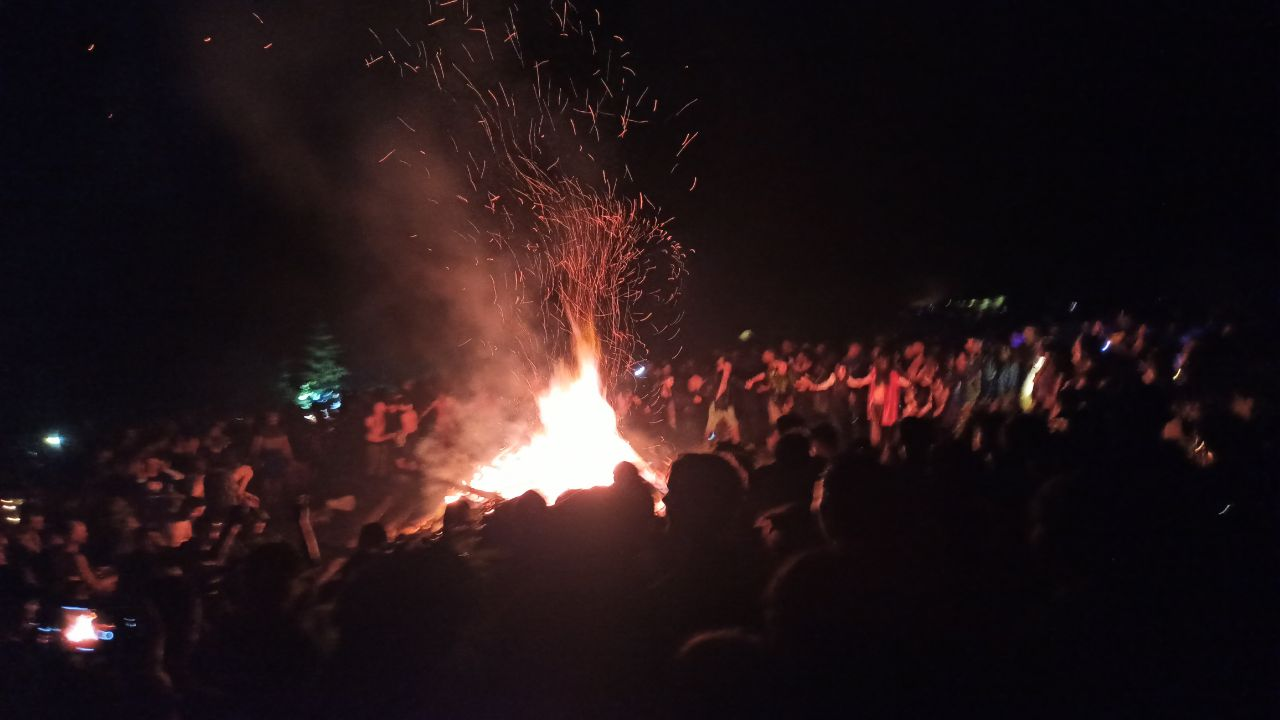

The festival has a core date, which is Ivana Kupala night. Interestingly, the date of Ivana Kupala will officially change in Ukraine now to be in June not July as they shift from the russian Orthodox calendar, though I believe the festival will remain on the same date for the sake of tradition. On this night, there is always a huge fire (Vatra in Ukrainian) where people dance around and jump across in a celebration, there are other traditions (such as the sacred fern, which only blossoms this night (in fact, I once met a man who claimed that he saw it once across a stream but injured himself while trying to get it). There are usually many people gathered, including locals just to observe the celebrating or get drunk and take part. No judgement here.

This wasn’t my first time, and I doubt it will be my last. My first time there was in 2019. My wife and I hadn’t been in Ukraine that long, in fact, she had been away for five years, and well, this was my first time living in Ukraine. We took the train from Kyiv and I had little in the way of expectations. All I knew was this was a truly wild festival: no organisers, no infrastructure (read: no toilets), just people gathering in the mountains.

I’ve talked a lot about the Carpathians in writing and that first time to the festival was my first experience of the mountains in the summer. Now, what may surprise some of you is that Ukrainian summers can get hot (and this is especially true the past few years, the last few days here in Uzhhorod it has been 33 degrees). But, as this festival is in a high spot, the temperatures are a lot more manageable, around 27 max in the day (usually closer to 23) though it can drop at night. That’s barring any rain and storms which are quite a daily occurrence. This gives a nice reprieve, especially if you lived, as we did, in an urban environment. In fact that year we rented a tiny Krushchovka flat with no aircon. It was far from comfortable, I’ll be honest, especially when you work online.

So when I arrived the first time, I was to meet lots of people my wife knew for years and experience something quite unique. You absolutely could not have a mass, unorganised campout in some fields, numbering thousands of people in the UK. What I discovered was a world of Ukrainians, many old-school hippies, but also people from all over Europe coming for this festival. It almost all spread from word of mouth and later on, some people made Facebook events. Usually, someone knew someone who knew about it.

I think many in the West may be surprised to know about Soviet hippies. Many lived in Lviv in the USSR, and many of them comprised the core group of people who attend the festival. They often have fascinating stories about what jobs they could do to avoid strictness on say the style or length of their hair, how they would get bootleg music, and how the movement was actually quite non-political for many. This is surprising in one sense as you’d assume they would be opposed to the oppressive USSR, yet on another hand, the USSR didn’t foster civil politics, and many Western hippies were equally apathetic.

I also found as there were attendees from all over Eastern Europe with connections to people who attend the festival, often the dominant language was russian. There were russians, Belarusians, people from the Baltics, and others who spoke russian and it was the russian language that gave them a common means of communication. This was distinctly noticeable the first time I attended, though this was less the case this year, with a more overtly patriotic atmosphere compared to the first few years I attended and more and more switching to Ukrainian. Obviously, there were fewer russians and Belarusians this year.

Some, though certainly not all, of the old Soviet-era hippies, in one breath, may mention being rebellious and tired of Soviet things when younger, but also condemn the West, make wistful comments about the USSR, and have no time for overt nationalism. They see it as divisive and perceive the great games played by politicians across the world as an enemy of togetherness. For example, at one point I said a popular expression “Yobana Rusnya” and one of the older hippies, with some of the most impressive dreadlocks I had seen, said this isn’t right, russians are not the enemy, it is politicians who divide us. Others certainly disagreed with him on this take, but I found it interesting.

It’s a contradictory amalgamation of views, no doubt. Certainly, I am not one to defend all politicians, or the Western governments’ actions in all cases, and do not oppose any idea of solidarity. Yet to romanticise a regime that often hated the sort of freedom they enjoy, seems quite strange to me, as it is to blame everyone, not just russia, especially in a time when russia is actively trying to destroy Ukraine, them, and them alone.

I do enjoy the mish-mash of Soviet and Ukrainian things to assert a distinct, non-soviet identity. This you can often find in Ukraine, especially among the more alternative people. For example, one man showed me his Soviet era cigarette case, with some famous Moscow building on it, but inside he had a picture of Mriya, the plane.

Generally, I found the first festival to be a relaxed space, where anyone can be themselves. Families, hippies, misfits, punks, whoever really, who wanted to come and experience the “vibe”. There’s no real judgment on who you are here, but, the main requirement is to be kind to each other, to share if you have extra, and to greet others with “good morning” regardless of the time of day.

I mentioned the poor reporting by Vice, but Ukraine had its own version of this sort of misrepresentation of the festival. I don’t know what year, but some guy from Ukraine wrote a book about the festival, and again, made it out to be some drug-fuelled orgy, where some punks from Ivano Frankivsk killed and ate a dog. He wrote under a pseudonym, though people worked out he was in attendance the year after the book. As revenge, people then decided to burn his book on the main fire.

The next year for me was the COVID year, although it did continue. It was a bit smaller than the previous time, and I felt a slightly different vibe due to the lack of foreigners which gave a different feel. At that time my Ukrainian was even worse, so I felt a bit isolated from more people. The year after, 2021, it had grown back, but now many more younger people camped down at the lower levels where we usually were. This is probably a good moment to explain the geography of the festival.

So the festival is named after a local waterfall, where tourist infrastructure has been rapidly growing. Even in 2019, there was one shop at the bottom, one restaurant, and a big hotel. It’s all changed now. But once you go past the checkpoint to the waterfall you walk up a hill. There are different “floors” of the mountain. The first floor tends to attract those older folks who have been there many years, families, so it’s a bit more mellow. The higher second and third floors have a slightly more youthful and chaotic vibe. I heard before there used to be “punk”, “hippy” and “metal” areas for different subcultures, though I can’t say that’s there anymore.

So in 2021, we stayed on the first floor, as we did previously, but more students took that area up, changing the vibe a bit. It’s not a problem, however, as someone who values sleep, it was a bit frustrating to have noisier neighbours 24/7 who never seemed to stop. Even when I was 20, mornings were always a challenge for me.

Nonetheless, it remained a great place. Not only could you enjoy the festival, but there is great nature for hiking, a river to bathe in, clean air, and beautiful starry nights, and you can really do whatever you want, stay as long as you want, and enjoy the festival how you want. Want to take drugs and go wild for several days? Sure! Want to just relax, appreciate nature, and go hiking? Sure. Want something in between? Whatever you want! There are no bands or any real events so to speak, though there are often spontaneous performances of this or that. Usually guitars and drumming, but there can be theatre performances, poetry, whatever, you just have to find them.

So I hope I have given a general explanation of the festival, and will now discuss my experience this year.

Typically, my wife and I would take the train to this festival. This was in no small part because of the immense distance from Kyiv. The journey was long, and the train did form a part of the excitement. Sometimes you would find other people who are going to the festival, share anecdotes about previous ones, and have a few drinks, all that. Once you get to the stop, a town called Volovets, you then need to find drivers (who, at the time of the festival, are waiting eagerly, and offering to take people to the closest location to the festival), wait for the car to be filled, and head off.

I recall 2020, when we all had to have masks to hand, while people were drinking and singing in the minivan already. It was certainly a strange contrast to the strictness we experienced in Kyiv during the initial phase of the lockdown. The police in fact stopped the van and made sure people had masks, but they were on as long as the policeman was there basically, before hanging around chins. I was not someone against masks or being careful, I was often frustrated with people’s disregard for precaution, but by that point, I had embraced the vibe of the festival and stopped worrying.

Once you arrive at the village, you then have to make the trek up the mountain, to find your spot. However, this year, we decided to take a private transfer. We realised that the time we would save doing this, and the cost of a train and then the transfer from Volovets would be negligible. Plus, we had far too much stuff for much walking.

In fact, we had three bags, mostly full of various interesting alcohol we brought. Our tastes had sophisticated somewhat beyond what the small shops of the village sold, and we wanted to share more interesting drinks than standard vodka and things like that. We had:

- Two boxes of pre-made gin and tonic (like box wine)

- Far too much slimline tonic

- Zubrowka

- Caramel Vodka

- Krupnik cappuccino liquor for coffee

- Vanilla vodka

- Cucumber vodka

- 2 litres of rum

- A selection of tonics

This in addition to a tent, sleeping bag, some food, camping things you generally need, and far too many clothes, in total all weighing about 30 kg. Thankfully someone met us when we arrived, a friend of my wife, to help us up the mountain. When we were younger before we met, both my wife and I often attended festivals with barely a change of clothes and maybe a bottle of something. We laughed at how we had gotten older and used to more comfort. But, we knew we were prepared. Our itinerary mostly involved hiking the mountains earlier in the week, then I would have a day of work at a hotel (unfortunately I couldn’t afford a whole week off) then we’d enjoy the festival as more attendees came in. This all fell apart for reasons we will get to. No, it wasn’t the alcohol.

The drive itself, to go back a bit, was pleasant, and we stopped with a stunning view of Volovets before doing the final stretch. Once arriving at the all too familiar village of Pylypets, the village at the bottom of the mountain near the Shypit waterfall, seeing our favourite restaurant “Grunok”, a feeling of true excitement and anticipation filled us. After being disappointed in 2021, this felt like we were defying the previous year, the russians, living our lives and where we belonged. Also, more personally, I really wanted to be in nature again and to just completely switch off from all things.

Despite the help of our friend, the hike was long this time, mostly due to the massive bags. We initially paused under a covered bench area at the bottom for one beer, before embarking with two relatively long pauses. The walk without bags, for me anyway, takes around twenty minutes or so. With this amount of weight, it was much longer. After climbing the mountain, we set up our tent quite low, with the potential plan to move it higher when friends arrived as they wanted to be further up the mountain. Why? Because last year people were served draft notices at the lower part of the mountain. A bizarre idea to draft people attending a festival. Many Ukrainian men actually were too nervous to come at all, so many attending were ineligible anyway. Though of course, some were, and thus wanted to be higher up the mountain. A tragic reality I Understand the necessity for, but it is tragic nonetheless. I do not believe in blaming the Ukrainians for this, I blame no one but the russians.

After setting up the tent with relative ease, we decided to have a drink, soak up the natural ambiance, and eventually head down to the village. We wanted this trip to get some proper food, buy any bits we wanted from the shop and head back up. This was when things went wrong. We walked down with no problems, me, my wife, and our friend, and took a shortcut to the restaurant where we wanted deruny (potato pancakes). At the end of the shortcut is a slight slope, and somehow my wife fell. I was behind her, and she took a while to get up, but our friend, who was in front, gasped. She had gashed her leg open quite badly and blood was coming out quite profusely. My wife insisted she was fine, in shock, and we headed to the restaurant we intended to eat at to sit her down, clean her leg, and see what to do. Of course, our friend and I agreed she needed stitches, and an ambulance was called. It would be thirty minutes, a far cry from the four-hour wait in the United Kingdom right now or whatever it is. My wife still wanted some food so we ordered food and I ate soup and drank a beer while waiting for the ambulance. Nearby were some deer kept in a pen, which were quite adorable. It was all a very surreal situation.

The ambulance came, they took one look at her and agreed to go to the hospital in the regional centre of “Mizhyria” which the paramedic assured us was a proper city, where we could return by taxi very easily and find whatever we wanted. The hospital experience was a bit different from the ones I had experienced, both for better and for worse….

The ride in the admittedly quite dusty ambulance was interesting, as three of us were in the back, as we navigated the villages and bendy roads. My wife had entered a shock-induced hysteria and was laughing at everything, and I found myself more nervous than she was. Nonetheless, we arrived at the hospital and immediately were brought in to be treated. None of the seven hours of waiting like in the UK (seriously, the NHS is in a bad state). The hospital was very Soviet, however. Bleak bathroom, dank corridors, and is definitely in need of some aesthetic renovation. However, this doesn’t comment on their efficiency or capability.

My wife would be stitched immediately, so I was sent to the shop in the village for the supplies we had intended to get back in Pylypets. Mizhyeria which was far from a bustling regional centre as the paramedic assured us, seemingly consisted of one street. Nonetheless, I got some supplies, including a lot of beers, after making friends with some owls in the hospital garden.

It is worth mentioning that this was not the first incident at the festival, a German guy cracked his skull open on a rock the day before, apparently. Though my wife simply fell on some grass and cut her leg on a mild slope. Not climbing the mountain, not drunk in the dark, no, in the early evening. So I guess they did have their work cut out for them this week.

I returned and she was already heading out. The doctor who treated my wife was having a cigarette out the window while we sat in the garden with a beer, organising a taxi. We then went to another shop after some time, my wife hobbling unable to bend her knee, and took the taxi back to the festival. My wife stayed with our friend, as she had a room in the hotel, and I went up the mountain. With no one around, and a need to decompress, I drank a couple of beers in the dark (it was around 11 pm by now) and decided to finish off The Sopranos, a show I had never watched at the time or until recently, and took myself off to bed.

The next day, I went down to the village to meet my wife, though this was after our friend camping next to us gave me some cognac in my coffee, on top of my Krupnik liquor. The original plan was to go hike to the mountain, but obviously, this was out the window now, and I didn’t know the route sufficiently, nor wanted to go alone with such variable weather. In the village, we all reunited at one of the longer-standing shops/cafés. They sold alcohol, beer on tap, food, and had a toilet, plugs for charging, as well as under-the-counter duty-free cigarettes of brands no one had heard of.

After assembling a sort of motley crew including two random Australians and a friend of our friend with cognac, we went to one place, then another, for food and drinks. My wife was adamant to return to the top today. Now we spent the day easy to ensure that she rested the leg, and left to go to the top around early evening. We managed to acquire a walking stick for her from a very friendly man running one of the tourist tat shops for free, one among many in the village. We also bought a hat for me, suitably patriotic. The man just said to bring it back when she was done with it but didn’t seem too bothered. In fact, we still have it, as we did, unfortunately, need it until we got back. Next year, perhaps.

We walked along the road to the checkpoint, which generally took around, ten, or fifteen minutes. It also seemed flat. That changes when someone is unable to walk properly. Our friend insisted she stays at the bottom, but my wife was more insistent she wanted to go to the top. Along the route, we stopped at a shop, on the invitation of two people there and the owner. “Shop” is a generous word, it was effectively a vendor operating out of a cupboard in a building. The fridges were there but didn’t work, however, the man was quite friendly and throughout the week would say hello to me and introduced me to his customers as “an Englishman”. The two guests at the shop involved a woman who lost her teeth in a fight at this very festival a couple of years back, and a rather dishevelled guy who had travelled to Mongolia, had some mushrooms with him which he traded for some weed off a passerby. He was speaking russian, to the chagrin of my wife who said, “If my husband can try to speak Ukrainian, why can’t you”. Nonetheless, we had an interesting conversation about how wildly different Mongolia is from anything else before walking back off again.

Eventually, we got to the bench area before the main hike up. My wife was still insistent on heading up, and I at that point completely understood that urge not to let something get in the way of plans. However, it was already approaching darkness. It was then that we met someone.

A man appeared who my wife immediately recognised despite the dark. I had met him before, he was one of the few people who lived on the mountain and worked in the hotels in the winter. There is a more solid construction built among large trees very high up, and they live as a sort of community. A rather eccentric man, as you can probably imagine from that description, who, as it turned out, was fighting in the war. As we walked, he told us the story.

He had gone to volunteer in the early days of the war to help. He assumed he would be tasked with something fitting his skills. However, after some initial volunteering, he was sent to do mining work. He spoke with much emotion about how horrible it was, how he wishes no one would ever go there. One comment that did strike me was when he said that if he dies, it means someone else lives. He told us several times that, if you ever have a romantic idea of going to the front, don’t do it. It is hell.

He also told us a story of how he raised funds for a drone, which, perhaps inevitably, was destroyed, and felt devastated about it. We told him it’s okay, it’s what happens, but it helped the effort. I asked if maybe there is some way I could help raise funds for his guys, but he insisted no. He also stressed that he only has two days off and wants to enjoy the festival, although I could tell he took the war with him and will forever.

We slowly hiked together and got to the “philosopher’s rock” as he called it, a central rock in the main field, which we often sat on at the festival. It was fully nighttime now, and a few people joined us for drinks. He couldn’t drink, as it is a condition for anyone in the army even on time off. After some further conversation about this and that, we went to the tent as we couldn’t find anyone. My wife realised the next day she should have stayed at the bottom, yet I am glad for this conversation. It reminded me, that behind every fundraiser is a feeling of guilt, behind every battle, there is a damaged soul. That war is not glamorous, that Ukrainians and other volunteers are dying and suffering day in, day out. I worry about the future, the damaged people returning from the war, with untold suffering and trauma, and how they will readjust into society. I do not have resentment for the Ukrainian government or army making horrible decisions such as drafting this poor guy, though I may think it’s not the best idea to take men like him. However, ultimately this is war, and decisions like that have to be made, and there are always people with poor decision-making skills higher up in any army or institution. Hell, every Ukrainian I met who is fighting has negative things to say about their commanders. Its war. Just remember, war is hell and we must share these stories, and help however we can.

After a slow morning of getting up, having coffee, and slowly walking down to the village, we headed to the hotel. This was a luxury hotel my wife always remembered as being something unobtainable when she was a young festival-goer not long after it was built. However, thanks to the war, the price was rather affordable, and the service and standard were incredibly high. After having probably the nicest meal I had ever had in the region, we checked in and enjoyed the facilities such as the pool, and I also did some work as was required of me.

Nothing much exciting happened here, though I did reflect on the contrast of relaxing here, not only away from the festival which felt like cheating, but in general, due to the context of the war. I feel every time you do something for yourself in Ukraine, far away, while people are fighting and dying, you feel guilt. Here we were, at a 4-star hotel, with delightful drinks, a pool, a restaurant, all that, while people are being bombed in their homes or fighting on the front. Yet at the same time, are we all meant to suffer? Are we meant to deny ourselves lives? Should we let russians rob us of every luxury we have? I think not, and by going to hotels, and restaurants, you are helping the economy which definitely needs help right now. Do we not help how we can? Do the soldiers ask us not to enjoy ourselves because they cannot?

Regarding the festival itself, is it perverse to celebrate like this, carefree and intoxicated while the war continues? For me, it is in itself an act of defiance, a statement that the russians cannot take everything away. That life must continue, that you will continue to live with freedom that the russians would certainly take away. To deny ourselves that, would be, to me anyway, to give in to fear. We all do what we can, or at least should, and it is not like we do not do our part to help. We fundraise, and donate regularly, I do my part in NAFO to combat disinformation, I write to encourage people to come to Ukraine and learn things they perhaps haven’t, and we are part of the Ukrainian economy. I certainly would be no use fighting, so we do our part. Of course, you always think you can do more, but you also have to take care of yourself and your family. The balance is hard, always, and people make their own decisions of course, and we cannot judge for that.

For those far away, who either are anti-Ukraine and bismerch Ukrainians and others daring to enjoy themselves or are pro-Ukraine and condemn anyone who wishes to not fight, it is easy for you to say. The war does become normalised, and you have a mix of emotions you can never understand unless you are here. Do you think people in world war two didn’t enjoy themselves? Do you think that those who didn’t fight were cowards even if they helped in other ways? It is very easy to say when it’s not your own choice to make. People are already under enough stress, including the pressure of themselves, why add to it when sat in the comfort of your peaceful country?

We extended the stay at the hotel to help my wife’s leg recover, though on Tuesday I decided to head up to the mountain to find our friends who were on the “third floor”. I walked in record time, and found myself among our Uzhhorod friends, watching the sunset, drinking some beers, and having conversations about a range of topics. There were two German friends of ours who do research in the Zakarpattia region and who came to record parts of the festival for research. We talked about learning Slavic languages, the difficulties there, and the challenges of never being forced to speak Ukrainian, which is why my level of Ukrainian is not as good as I’d like. At this point, my understanding is quite strong, but my own speaking is considerably worst, in part due to a lack of vocabulary but a lot due to grammar. Once I have had a couple of drinks I gain further confidence and power through the mistakes I have noticed.

After watching the sunset and spending a bit more time, I headed down to sleep in the hotel bed and shower, taking advantage of the facilities before leaving the hotel to come back to the festival.

On Wednesday we utilised the hotel facilities as much as possible, eating their buffet breakfast, showering, and that sort of thing. The day was leisurely, staying at the bottom for most of the early afternoon, and having lunch with some of our friends who made their way down, before heading back up. We made the journey to the third floor, my wife just about managing, and then exhaled: I had finished work, and we could fully embrace the festival, turn our phones off, and just relax.

Some friends of ours decided to go to the very top level, which was around a thirty-minute walk from the third floor. I had never even known people camped up there, but as I said, people were going higher up this year to avoid drafts. I decided to go along with them to experience what was happening, and our German friends were planning to record what was taking place for their research.

Along the way, I spoke to one of our friends, who has been since the very beginning. He told the story as we walked through the forests up the mountain.

“So, I know you hate being interviewed with questions about the festival” (I had seen him several times be badgered by wannabe journalists and visitors to get insight into the festival’s history and his annoyance with it after some time) “But can I ask you?”

He laughed, and said “Yes, you can”

“So..how did it begin”

“Well, in the late 80s, it was the USSR, and many of us would meet up in Latvia for camping when it was Ivana Kupala. This time had a bit more freedom to do that than before as you may know” (so you understand, we’re talking late Gorbachev era)

“Sure”

“It was around 20-50 of us and one year, we had a trip to this spot, just as an extra holiday, and decided, this would be here we would celebrate the Ivana Kupala night from now on. The funny thing was, next year, when we came, in 1993, we thought “Huh, it’s a lot steeper here, and the meadow is a lot smaller””

“But you decided to continue”

“Yes of course. Then, just each year, it grew, more friends of friends, and their friends and so on”

“Which was the biggest year?”

“Probably…2008”

“Oh really”

“Yes around 9000”

“Oh, how has the festival changed”

“Well since covid, since the war, of course, it is smaller now”

“But has the vibe changed, the atmosphere”

“Yes and no, it’s quite hard to really say. It’s bigger than when we started.”

I am always impressed with the ability of Ukrainians to state the obvious back to you with impressive sarcasm.

“Do you think it will continue?”

“Well, maybe not if someone buys this land”

“What then, go back to Latvia”

One of our friends interjected, who spent time in Latvia

“In Latvia you can’t do this. Too many rules. No camping in national parks”

“Ah true”

I should explain, there was a rumour a few years back, that someone was buying the land to do…something, I don’t know, a resort, etc. But nothing came of it.

What I find fascinating in this conversation is how in Latvia, it is the government who could forbid this sort of thing, in Ukraine, it is the private landowners. This is fascinating when we consider the history of the USSR and the idea of private property and its connection to freedom. Within the USSR, private property had different roles, such as encouraged (NEP era under Lenin), permitted (Gorbachev), barely tolerated, or downright outlawed (the latter under Stalin). Of course, for many, the dream of property ownership is an idea of freedom. This is in many schools of thought as well, as a way to be independent, free from the government, and to exercise your skills and pursue your dream. But, whenever someone, an individual, or a group, owns something, there is a degree of exclusion as it means someone else cannot own or maybe use it. Here, now, in 2023 Ukraine, the threat to freedom may come as much from the rich as it does from the state. This is why it is important to have public spaces, or a right to roam, alongside private property to balance the tyranny of the state or domination of the wealthy. But should the state forbid people perhaps abusing nature? To protect it? Possibly, but the thing I think of is how in the UK, we depend on the state and are used to them making decisions and infrastructure for us, and wouldn’t be as sufficient at self-organising as at Shypit perhaps, or we would, but we cannot try. I have no real answer here, but it is a lot to reflect upon…

Speaking of owners of local land, there is a rather bizarre, and quite worrying, situation regarding one of the main attractions. There is a mountain that in the winter serves as a skiing location, but all year round you can take the ski lift to the top, enjoy the views, go to the restaurants at the top, and it obviously brings in quite a lot of people to the area. Two men owned the land, and one wanted to sell, but the other did not. Rather than coming to any amicable agreement, they both ended up tearing it all down, somewhat literally and metaphorically, leaving the restaurants in the lurch, and removing the opportunity to ski in the winter or visit the top. To me this demonstrates the precariousness of these regions, the reliance on tourism, and how sometimes individual pettiness can be the main cause behind disastrous decisions.

Going back to my trip, at the top, I found a totally different vibe to the relaxed atmosphere lower down. A large drum circle with many people dancing dominated the atmosphere and was noticeable, and predominantly young people were gathered in tents all in close proximity to each other. It reminded me more of the youthful decadence of the festivals I attended when younger, and a little of the first Shypit I attended as well. We had just missed some theatre performances as well. In some sense, I felt I was missing out by being far from here, but on the other hand, I wondered how well I would sleep up here, and whether I would really want to be either committed to staying up here or going back and forth almost an hour or so to the bottom. No, is the answer.

My German friends took it upon themselves to record interviews and the ambiance, from what I vaguely understood it was a mix of answers as to why people attended, which in my experience tends to revolve around that they can be themselves, that they can be in nature, remove themselves for a few days from the daily life, which now had the ongoing background of war. There are no bombs here, no sirens. The sense of war is there, with the stories of those who have fought, the ones lost, and the dread of returning home for some, yet, here, people go to be themselves.

I found the Australians we met at the bottom, and after talking attracted multiple Ukrainians who overheard our English, and asked us the usual, and less usual, questions that any foreigner gets. “How did you learn about this place?” “Do you like Ukraine” but also more recently, “Why have you come to Ukraine now?” of course. It was interesting as I have attended more than many of these people. I was offered some terrible wine as I ran out of my beer, a sugary syrupy “local” wine which is definitely not made of grapes sold everywhere in the mountains with fruit flavours and gives you the worst headache of your life. This tided me over and I appreciated the sharing culture was strong. I did give pour some beer into a guy’s cup as well which is why I ran out. Circle of Shypit.

After the speaking club at the top, I eventually returned with several friends. Continuing drinking, and eventually catching up with the Germans on their findings (and that they wished they caught my conversation earlier), we slowly headed down to our tent, making sure my wife didn’t fall. We sat by a drum circle, and something about the day, the hiking, the heat, the drinking no doubt, and the melodic drums, sent me to sleep by the drum circle at around 2 am. We eventually stumbled back to our tent, after almost missing it, and slept well.

The next day was Vatra day. My wife was worse for wear as we say, and I wasn’t feeling brilliant either. It is very typical to overdo it on the first day of the festival proper, and well, we did just that. After making another alcoholic coffee to embrace the hair of the dog, it was decided that I would head down, buy supplies, and meet my wife for something to eat with the others.

Nothing was amazingly exciting on the way down, but my plan was to meet my wife at “Grunok” eventually, and prior to that, find my British friend who was arriving from Uzhhorod. I ate a hot dog on the way, the fantastic hot dogs you can only seem to find in eastern and Central Europe where the sausage is placed into what can best be described as a bread tube. I ate probably around 10 of these over the week from the vendor right at the bottom. I went to the shop, stocked up on beers, and waited for the friend to arrive. After sitting with a beer her arrived, and we headed up to his accommodation (cheater!) and then to Grunok. Not only did I find my wife on time, but we saw a friend of ours from Mukachevo, an older guy who had moved to Ireland since the war started, an old soviet era hippy too, and had amazingly even switched to Ukrainian. His family was now in Ireland, apart from one of his daughters, and he often went back and forth (he was over the recruitment age). We also met an American and his Ukrainian wife, friends of his, and our friends joined us too, meaning we spent around four hours at Grunok, eating Carpathian food and drinking a few beers. We even had a guitar and I played a combo of British and Ukrainian folk songs, including Hey Sokoly.

What makes me sad about Grunok is that only two people run the place due to the war, the main son who we first met now in Poland with his Polish wife, leaving not long after the war, and the daughter, his sister, and mother are clearly under pressure. Nonetheless, I hope that weekend brought them some income, and if you ever find yourself there, please pop in.

Due to my wife’s leg, we decided to cheat a bit and take one of the horrible four-by-fours up to the top. A business we absolutely despised which has been going on for a few years. We always judged the participants of this business, but in this case, with her leg as it was, and the rush to get to the top for the big fire, it seemed necessary. So we did just that.

It was already heaving up there, which made it considerably hard to find people. The fire was just beginning, but it already had a huge audience. We had heard a rumour the fire would be elsewhere and this one smaller, but this didn’t seem to be the case. Though we did later find out there was another fire elsewhere, clearly not to the detriment of this one. That was the case last year, with a dummy fire for those unable to be recruited attending, and those eligible higher up at a different fire.

People were everywhere, and it was extremely difficult to work out where friends were, and it turned out I was close to finding some but missed them. People would start conversations randomly with you, and they shared drinks with you and asked for drinks, it was a truly communal experience, and I think it had an extra component this year. Coming together to watch this fire, see people dance around (even sometimes naked), celebrate, and gathered en masse, is a truly spiritual experience. This old celebration going back to Pagan times, which presumably changed dates with Christianity, indicates the pagan roots of Ukraine and how paganism merged quite clearly with Christianity. But more than this overanalysing, it is a spiritual experience to gather with people, which many in Ukraine have been denied, or at least denied doing so safely. This is precisely why these experiences are crucial, it is a human need to come together and enjoy something. Religious ceremonies, musical performances, and whatever else, all serve the same purpose.

After some time though, the rain came, and some of us gathered under a tarpaulin-covered area, with chairs and table and fire, of some people we knew. Here is where we managed to find everyone we knew, as they had the same thought. We did lose a bottle of rum at this point after sharing it with some random people, and we were all eventually told to leave as there were too many of us, but this was a ruse to get rid of people the owners of the area didn’t know. We stayed there late and frankly, it has all got a bit blurry, but I know I had a good time. After eventually going back, and soaking the tent with my wet clothes, we felt we had truly enjoyed the festival with one full day left.

The final full day arrived, and my wife decided she would stay in the hotel to rest her leg properly and be dry. A desire I fully understood but I needed to stay up at the top to ensure the tent was packed, things were dry enough, and we were ready the day after. The day was leisurely, we first sorted a hotel. Here the owners were suspicious of people not staying using their facilities, which I did sneakily do, as well as napping in my wife’s room, and my cover was that I needed to help her with her injured leg. Frankly, it’s not like the facilities were any good. I’ve had better showers in the dingiest hostels and campsites. Hotel was a glorified word for a tatty house with basic rooms, where they charged quite a high amount. You can pay ten euro more for an actual semi-decent place. High demand I suppose. After we ate some food, and eventually, I left back up to the festival space with many people leaving, yet others arriving still. I did not want to indulge as heavily this day, to avoid packing the tent up hungover, so went to the top with friends and relaxed, watching the sunset over the mountains.

Eventually, I headed back down, and it was quite early. I went to the scene of the crime the night before, yet they were also heading to bed. I was alone, with a lot of alcohol I needed to get rid of, as we had not made as much of a dent in the alcohol as we expected, and no one I knew around. I first investigated the fire, yet the crowd seemed quite insular. Very different from the atmosphere of the day before. I had no willing to go to the very top in the dark by myself on the off chance of finding people, but I did see a group of people playing music with a relatively large audience. I went over, hoping to find someone to strike up a conversation with and offload this booze, but people were transfixed on the music (they were playing Gogol Bordello’s Start Wearing Purple), and eventually, just as I was about to give up my quest and abandon some alcohol, someone asked me for a lighter. They understood I was foreign, and we chatted, in Ukrainian I might add (tipsy confidence to the rescue) and I offered them some alcohol. Sure, they said. Then some others arrived. They were quite young, early twenty-somethings from Ternopil. They had just arrived that day. After I explained I had a lot of alcohol, they invited me to their camp area, “Great” I thought.

Well, what actually happened was then they offered me alcohol to demonstrate Ukrainian hospitality. There was a guy who spoke great English and between my elementary Ukrainian, his decent English, and others’ basic English, we talked about this and that, mostly why I was there, why I liked Ukraine, and other questions they had for me. It was their first time, and they just wanted to experience it, yet I highly appreciated these students respected the share and share alike attitude of the festival. After almost forcing them to accept a bottle of rum, and sneakily leaving one for them, I headed back to my tent, with offers to walk me back from them for my safety, despite the fact I was a whole three minutes away.

The next day I awoke at 7.45 because my friend stayed at the top and came down, as promised, to help me pack the tent, blissfully unaware of how early it was. I had initially planned to sleep till nine or ten. He however stayed without cover of the sun. Yet it did help motivate me to pack quicker, and he was still in fact drinking, so I offered him some booze for cocktails to finish off the remaining alcohol as he clearly hadn’t stopped partying (though some remained after everything and is still sitting in my cupboard), and we headed down, pausing often with my heavy bags and reflecting on the experience. Eventually, we made it to the hotel, went back to Grunok one last time, and were picked up by our driver and headed back to Uzhhorod. After multiple goodbyes to those we saw, and implicit ones to those we didn’t with the hope to see them again. By this point, I was ready for an actual bed, at home, and being dry and sober.

So, as a final note, I suppose I said everything I wanted to. Shypit is an experience like no other I have had. A gathering of all sorts, in the mountains, to come together, take what they want from the festival, to be actually quite safe (falling over nothing and cutting your leg or perhaps getting too drunk notwithstanding), to be free ultimately, and themselves. I do not know if I can attend next year, but I will be back for certain, and I urge you to one day consider experiencing this.

Leave a Reply