Imagine you’ve been studying English as a foreigner (which is going to be a sizeable number of readers), and you end up living in Newcastle. Or Liverpool. Or actually, a lot of places in the UK. Or parts of the USA or any English-speaking country. Rarely does language sound as it is taught, and not all countries have “one” version of their language, and if so, we have to be mindful of this. One such place you can experience this as a Ukrainian language learner is in Zakarpattia/Transcarpathia.

I recall a time, in 2020 or 2021, it was during COVID, but after the worst period, when some travel was permissible. My Ukrainian wife and I had taken a Bla Bla Car to one stop in the mountains, to then take a bus from a nearby village to our destination. We got out of the car, and our backpack’s straps snapped. We were in the middle of nowhere. There was a simple checkpoint for COVID-19 vaccines with a police car, as we were on the border of Lviv and Zakarpatska Oblasts, a small grocery shop, and some sort of other shop.

We slowly walked in the direction of the shops, and a woman came up to us. She seemed to offer to help, from my perspective, but I couldn’t follow what she was saying. At this point, I had some understanding of Ukrainian, even if my own speaking was limited, yet I was unable to follow a single word. I assumed it was just me. My wife, on this woman’s advice, went to the other shop with the women and then to get some small ropes, as a thank you, went into the small grocery shop to buy her cigarettes on her request. Meanwhile this woman, who i could tell was severely autistic or had some other neurodivergence or developmental disorder, was chatting to me very enthusiastically, and the only thing I understood was that she dubbed my wife a cute name on account of her then blue hair “Sinyavka” (like little blue one). I just smiled and nodded the whole time. After we got on a bus, I said to my wife, “I didn’t understand a word.” “Oh, it’s not you, I couldn’t either”. Now, I live in Zakarpattia a lot of the time, and have become used to many phrases from the region, forgetting they are not common across Ukraine.

Dialects and accents can make the experience of learning any language a real challenge. Ukrainian is no exception. Now, Ukrainian doesn’t have the wide array of accents that English does, mostly due to standardisation. Polish similarly has even fewer accents, aside from the mountain regions, due to the development of a standardised language being relatively “late” due to the lack of statehood for a considerable period.

However, there are multiple dialects and accents in Ukrainian, some, especially in the East and South, are nearly extinct. In contrast, Galicia (Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk) and Zakarpattia/Transcarpathia have distinctive and widely spoken variations, with sub-variations.

Note, I am trying to be careful not to weigh in on the dialect vs language debate here, I will get to that later.

In Zakarpattia, more akin to my experience growing up in England, you don’t have to go too far to get shifts in accent. I am not, by the way, talking about language diversity, which is significant in the region, but I am discussing Ukrainian language dialects. There are Hutsul, Boyko, dialects; there are variations in the north, south, east, centre, and west. If you’re in the mountains proper, you will hear very thick, hard-to-understand versions of Ukrainian that even native Ukrainian speakers do not understand. Different regions have their own words, stresses, endings, etc, and it can even vary from one village to the next, due to historical factors (what groups lived here, etc). It’s almost hard to generalise about a “Zakarpattian” dialect at all, really.

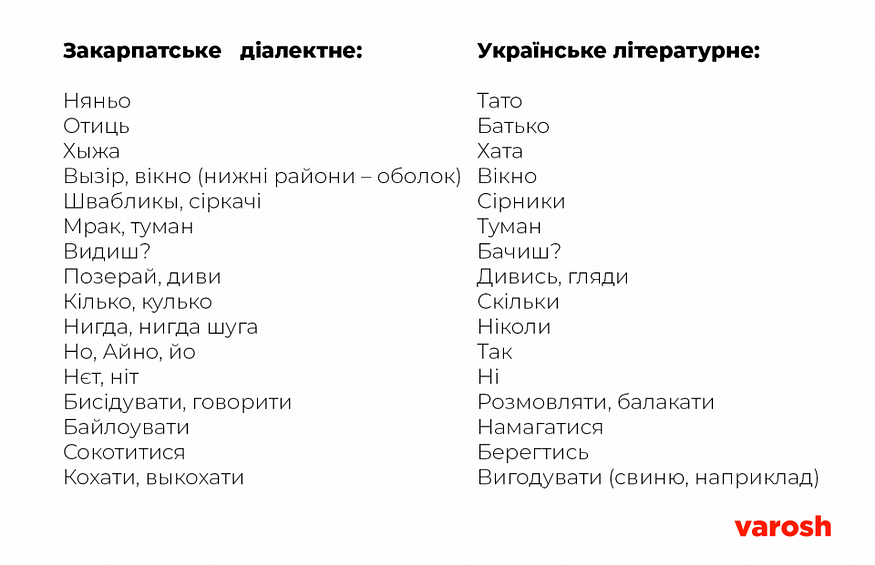

Despite that, there are some examples of very Zakarpattian words that you can hear across most, if not all, the region:

- Matsur/Matchka — Cat (this is basically an adaptation of a Hungarian word)

- Nych- Nothing

- Hodynka — Clock

- Varosh — City

- Faino — Good (This is also common in Galician and Ukrainian)

- Aino — but yes

It’s quite hard to write them up into English, as they often feature the soft sign, a pain for any Ukrainian language learner, such as myself.

Now, what is interesting is that some, like Matchka, clearly come from Hungarian. Some villages might use German loan words due to the presence of Germans in the late 19th and early 20th century. Of course, we can also have words from Polish, Slovak, etc. But some are just very unique terms. There’s even the term “амбрела (ambrella) for umbrella in some places!

So there are a few of many unique local words. What else can be different?

A lot, and it’s quite complex to explain without a core understanding of Ukrainian, and even then, there’s a lot of complex linguistic research. But, in brief, there are different sounds, Ukrainian has і and и, russian has и and ы, the local dialect has all three as separate sounds. Just to give any learner a heading. There are suffixes, such as “iv” here, that you do not get in standard Ukrainian, so instead of “Ya idu do doma” (I am going home) it’s “Ya idu domiv” or instead of “vse dobre” for all is good, it’s “vse dobriv”. Some reflexive verbs have prefixes instead of the typical suffixes in literary Ukrainian.

However, as soon as we start taling about this topc, we touch on the rich history of a mountainous region, which is always unique in any nation, which has had multiple empires and nations rule here, and also, a political debate around whether or not it is truly an accent, a dialect of Ukrainian, a dialect of Rusyn, or Rusyn itself. It’s almost impossible to discuss language without weighing in on a controversial topic in Ukraine.

The dialect or language has been categorised differently by different persons and governments, and research continues to this day on the topic.

I’m not a linguistic expert, so I cannot say my perspective on this. What I can say is that it is important for us to try to be sensitive and understanding, and there is a lesson as well that Ukraine’s language realities are more complex than many would like to portray. Zakarpattia has often been a periphery of whichever empire owned it, and yet it has an incredibly rich history and is worthy of study and the identity maintained by its citizens.

To promote an overly narrow idea of a language is to overlook regional and linguistic diversity, all of which is a part of a nation. To make sweeping generalisations, like many many so-called “experts” on Ukraine do i.e., “Russian-speaking east vs Ukrainian-speaking west” fails to understand the realities of how language works, of the history and complexity that arises trying to understand language in Ukraine and other countries. Language is everything; it can serve as a foundation of a nation, of our own perception of reality, of how we consider ourselves. It changes all the time, borrows, adapts, dies out. Zakarpattia is a representation of a region wherein we can see a different sort of Ukrainian, that is nonetheless fundamentally Ukrainian.

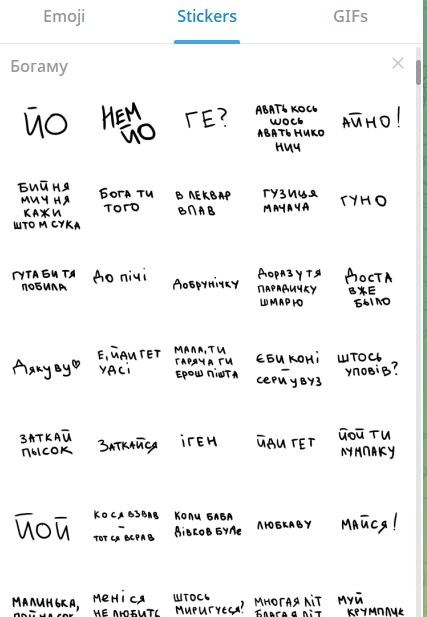

So, yes, it is fun to learn a lot of new phrases in a regional dialect like Zakarpattia, and I encourage it. But, it’s a way to learn the history of the region, and consider the future.

Some further reading:

https://www.academia.edu/50731245/Carpatho_Rusyn

https://starapravda.com.ua/en/blog/zakarpatskyj-dialekt-yak-rozmovlyayut-guczuly/

Real linguistic stuff, but in Ukrainian: https://esu.com.ua/article-14618

A dictionary, which I’m not 100% on being correct: https://web.archive.org/web/20140118000722/http://words.eugene-home.kiev.ua/

Leave a Reply